By Mark Golitko, Associate editor in lithic and network analysis

This is my first blog since being asked to serve as associate editor for lithic analysis and network analysis. It is somewhat delayed due to the global pandemic and the strange adjustments we have all had to make (teaching and conducting all business online in my case). The spread of Covid-19 itself, and the rapid dissemination of fake news and strange conspiracy theories surrounding the virus have served to highlight the complexity of the global human network to which we all belong, such that a virus that jumped to the human population somewhere in Wuhan, China, reached South Bend, Indiana (where I currently sit writing this) after only about two or three months.

Posted by Carmen_Ting on July 01, 2020

By Mark Golitko, Associate editor in lithic and network analysis

This is my first blog since being asked to serve as associate editor for lithic analysis and network analysis. It is somewhat delayed due to the global pandemic and the strange adjustments we have all had to make (teaching and conducting all business online in my case). The spread of Covid-19 itself, and the rapid dissemination of fake news and strange conspiracy theories surrounding the virus have served to highlight the complexity of the global human network to which we all belong, such that a virus that jumped to the human population somewhere in Wuhan, China, reached South Bend, Indiana (where I currently sit writing this) after only about two or three months.

This is my first blog since being asked to serve as associate editor for lithic analysis and network analysis. It is somewhat delayed due to the global pandemic and the strange adjustments we have all had to make (teaching and conducting all business online in my case). The spread of Covid-19 itself, and the rapid dissemination of fake news and strange conspiracy theories surrounding the virus have served to highlight the complexity of the global human network to which we all belong, such that a virus that jumped to the human population somewhere in Wuhan, China, reached South Bend, Indiana (where I currently sit writing this) after only about two or three months.

Interest in studying the structure and consequences of human social networks are nothing new in archaeology, and can probably be traced back at least as far as diffusionist models during the discipline’s culture historical phase. However, as nearly every paper employing network analysis in archaeology during the last decade or so mentions, “networks are gaining popularity in archaeology.” That said, there remains considerable debate about the utility of methods and ideas drawn from Social Network Analysis and Network Science, as highlighted in a number of recent publications that I would like to draw attention to in this post.

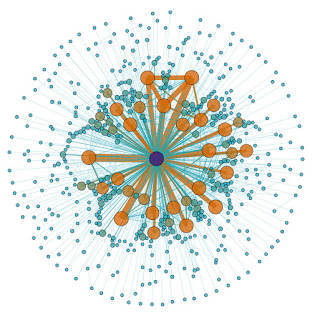

The first is a volume entitled Social Network Analysis in Economic Archaeology-Perspectives from the New World, (Rudolf Habelt, 2019) edited by Tim Kerig and several then graduate students from the University of Cologne. This volume emerged from a workshop held at the university in July of 2015—disclaimer, I was a participant at the workshop and have two papers in the book (and provided the cover image), but I won’t be discussing my own work here, which is largely a rehash of thinks I have published with my collaborators in the past. The workshop (held over two swelteringly hot days) paired more senior researchers with graduate student moderators to discuss the practice and utility of networks in archaeology. While papers dealing with European archaeology were also included, the volume focuses only on papers dealing with archaeology of the Americas. Of particular note is a paper by Jessica Munson, who asks what it is that we actually are reconstructing when we generate networks from archaeological data. She provides a useful classification of “edge” types drawn from work by Steven Borgatti and colleagues, and her chapter should be read by any archaeologist interested in critically using network analysis or concepts in their own work.

Archaeological Networks and Social Interaction (Routledge, 2020), edited by Lieve Donnellan, contains a series of papers first presented in a session at the 2017 EAA meetings in Maastricht (I was in the audience). This volume critically explores the potential parallels and conflicts between Social Network Analysis and other relational perspectives like Actor-Network Theory (ANT), Entanglement and Assemblage theory, and the “New Materiality.” In particular, many of the authors explore the differences between network representations and the ethnographer Gell’s use of “Strathernograms” (derived from the work of Marilyn Strathern in the New Guinea highlands), another way of graphically mapping social links and their content and contexts. The first substantive chapter by Carl Knappett is a good summary of these perspectives and possible ways to link them to the archaeological record, but the volume as a whole presents a growing tension between the use of formal network methods and existing relational theoretical perspectives employed by archaeological practitioners.

There are two journal articles I would also like to make readers aware of. The first (Gísli Pálsson—Cutting the Network, Knotting the Line: a Linaeological Approach to Network Analysis) published earlier this year in Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, critically examines the applicability of formal network approaches to historical records of social and economic relationships in Medieval Iceland (and was also first presented in a session at the 2017 EAAs that I took part in). Pálsson suggests that ordinary SNA methods have difficulty dealing with the complex and dispersed nature of human social connections, an idea also explored extensively in Archaeological Networks and Social Interaction, in which Strathern’s idea of the “dividual” is extensively employed to question the idea of representing individuals as static network nodes. Both those papers and Pálsson’s strive for a more nuanced and complex way of representing the position of individuals in complex webs of interaction, as well as examining the consequences of positionality.

In her paper Network science and island archaeology (2020, Journal of Island & Coastal Archaeology), Helen Dawson explores the utility of network science for moving island archaeology in the Mediterranean away from the “Island Laboratory” paradigm towards a new relational understanding of island identity and social development. In particular, she explores the concept of “categorical” versus “relational” identities in interpreting the archaeological sequences of islands. This paper reflects an ongoing debate in the archaeology of coastal and maritime places as to whether islands can be treated as model social systems developing in isolation from one another, or need to be considered as networked places linked to other islands and mainland communities.

What links all of these other than a general critical examination of the role of networks in archaeology? There is clearly a desire to move away from categorical representations of the past to a relational perspective, in which the properties and outcomes that we as archaeologists study (i.e., style, social change, economic change, and so forth) can only be viewed in the context of the relationships that past actors were embedded in. These works also reveal that there is a considerable amount of disagreement about how to most effectively make this switch in thinking. While this is certainly a healthy trend in the broader theoretical world of archaeology, I do find it worrying that archaeological approaches to relationality seem to becoming more and more insular to the discipline. For instance, in her introduction, Donnellan argues that a basic issue with network analysis is its inability to handle difference of scale between the individual “micro” and broader social “macro.” While this is an issue with archaeological data in general (particularly the “micro” part in my estimation), I find a statement like this difficult to apply more broadly. Network approaches in a sense are defined by an interest in exploring how “micro” dyadic and triadic interactions generate macro-level structural tendencies, and how these macro-level tendencies in turn impact micro-level social outcomes. Similarly, concerns that individuals in non-western societies exist only as relational entities dispersed across their social network links would seem to mirror much work in the broader realm of social network analysis, which demonstrates how individual social outcomes like propensity for smoking, obesity, or other likes and dislikes can be shaped by local social “neighborhood” structure. This is not to say that SNA and network science has all the answers, but I fear that in becoming overly inward looking, archaeologists interested in using relational thinking to answer significant questions about the past may be too quick to discard what is useful along with elements of SNA that may not be so easily applied to the archaeological record.